Queen Mab isn’t just a fairy. She’s a fairy queen, presiding over dreamland, drawn in state by a fairy coach, trailed by attendants and servants. She makes her literary debut in Romeo and Juliet, when Mercutio erupts into a fanciful speech about Queen Mab as the ruler of dreams. Her real origin is obscure, since nobody has been able to find a clear reference before Shakespeare. The name “Mab” is Welsh, and may represent an echo of pre-Christian Celtic mythology. In Ireland the great goddess Medb was transformed into the legendary Queen Medb, cattle thief extraordinaire. It’s quite possible that the same Celtic goddess underwent a similar downsizing in Wales—except instead of becoming a mortal queen, she became a fairy. Whatever the case, it’s likely that Shakespeare was drawing on existing tradition in the folklore of the British Isles.

For the costume, we imagined Mab in a medieval ensemble that would have seemed exotic, fantastical, and archaic even in Shakespeare’s day. It looks complicated, but it’s really just a matter of layering. The items we suggest, from left to right:

For the costume, we imagined Mab in a medieval ensemble that would have seemed exotic, fantastical, and archaic even in Shakespeare’s day. It looks complicated, but it’s really just a matter of layering. The items we suggest, from left to right:

1. Holy Clothing Miranda top in sage layered over bright red arm warmers. If the Miranda top is no longer available, the Trinity top is similar.

2. Three-layer skirt in pink/green/orange. The skirt we originally used for this costume was called a “three tier color fusion,” and it doesn’t seem to be readily available anymore. You can still get solid color versions at Belly Dance Digs.

3. Large red fairy wings. These are adult wings, not kid size, and they’re sometimes sold as “fantasy” wings or even devil wings, though they’re really not. They don’t have feathers; they’re supposed to look more like insect wings (organza stretched over wire). You can also look for butterfly or tinkerbell wings, like these.

4. Pink “princess hat” (hennin). This hat is about 16 inches tall, so it’s not quite as huge as it looks in that rather weird picture from the product vendor. The veil that comes attached is kind of dinky, so we suggest you replace it with a yard of chiffon (next). Just pin it to the tip of the cone.

5. One yard each of peach chiffon, fuchsia chiffon, and tangerine chiffon. Pin the peach chiffon to your hat as a veil. Wrap the fuschia and tangerine chiffons around your waist as a two-tone sash.

6. Autumn fairy wreath, autumn fairy wand, and English Ivy garland. Fit the wreath around the base of your hat. Pull the flower/ribbon arrangement off the wand and pin it to the front of your sash. Pin the English Ivy around your neckline, sleeves, and wherever you need some greenery.

More on the headgear situation: The only tricky thing about the costume is keeping the hat on your head at a backwards slant, which is how it should be worn. Good old-fashioned hatpins will work as long as you have enough hair and you’re not planning on doing handstands. An alternate approach is to pin a couple of sheer ribbons to the hat and tie them under your chin.

As for the veil, just pick up the yard of chiffon from the center—like a napkin or handkerchief—and pin it to the top of the cone. It will drape very prettily. There’s no need to hem the chiffon, but the edges will definitely fray a little bit. If that bothers you, you can seal them with Fray Check.

Main illustration credits: The large painting is Fairyland (1906) by Edward Reginald Frampton. The image on the right is a page from The Great Encyclopedia of Faeries by Pierre Dubois, published in 1996, with illustrations by Claudine and Roland Sabatier. The figure wearing the hennin is an Enchantress, whom Dubois describes as a regal fairy-like being often connected with Celtic mythology on the Continent.

Long ago, before Venus or Aphrodite, before Artemis or Athena, before Demeter or Persephone, there was Inanna. She was the great Mesopotamian Queen of Heaven and Earth, the goddess of love, fertility, and war. Inanna was what the Sumerians called her; their Semitic neighbors, the Akkadians, called her Ishtar. As time went on the Sumerian language was entirely replaced by Akkadian, and thus Ishtar is the name that endured. It was as Ishtar that she was worshiped by the later Babylonians, the Assyrians, and the Canaanites, who pronounced her name something like Ashtart. When the Greeks came along, they rendered her name as Astarte. In one form or another, she was the face of God for 4,000 years.

The early images of Inanna-Ishtar show her wearing a flounced dress—a kaunakes—which was a super-archaic Sumerian garment with long tufts of wool pulled out to make it look like a sheepskin. Over time, the kaunakes was replaced by a shawl-like tunic wrapped spirally around the body, and the long wool tufts evolved into fancy fringes along the border of the cloth (as you can see in our main illustration above: look at how the people of the Neo-Babylonian court are dressed). For our Inanna-Ishtar costume we’re going with the fringe-on-cloth version rather than the archaic sheepskin look. The blue is a reference to the lapis lazuli that was sacred to Inanna, and to the blue-glazed bricks of the magnificent Ishtar Gate. The other key goddessy components of Inanna-Ishtar’s outfit are her horned headdress and her wings. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Blue sari. A modern sari is a perfect substitute for the ancient Mesopotamian spiral tunic. Saris are typically at least five or six yards long, which means there’s plenty of cloth to wrap around you several times. (We give you some tips below on how to wear it.) There are a million blue saris in the world; you can look for a vintage one on ebay or buy a new one. (Ours is a vintage sari that we found for 20 bucks.)

2. Gold fringe. You’ll need five or six yards of fringe to attach along one edge of your sari; just use something like Res-Q tape to stick it on.

3. Maleficent horns transformed with Krylon Fusion Blonde Shimmer spray paint. It’s not easy to find Bronze Age divine headgear in the costume shops, but this year we’re in luck: Disney’s Maleficent was a hit, and the stores are full of long, curved horns that are just the thing for Inanna’s crown. This particular set of horns is simply held together with string, so you can turn them around and wear them at a different angle. For Inanna, you’ll want them curving towards the front; we tied ours together in the front with invisible thread. The Krylon Fusion spray paint does a good job on the plastic.

4. Eight-pointed royal blue star. The eight-pointed star was Inanna’s symbol par excellence. It signified the Morning and Evening Star—the planet Venus—which was Inanna’s celestial manifestation. We cut one out of royal blue glitter foam, and attached it to the invisible thread holding our horns together. Here’s an outline image of an eight-pointed star you can use: 8-Point-Star-528px.png. Just print it out and trace it onto glitter foam or cardboard.

5. White feather wings. Not all depictions of Inanna-Ishtar show her with wings, but she could clearly sprout them whenever needed.

6. Blue beaded medallion necklace. In the Descent of Inanna, an ancient hymn describing the goddess’s trip to hell and back, it says that “she hung small lapis-lazuli beads around her neck.” So wear a blue-beaded necklace of some sort. This bib-style piece from Zad looks appropriately fabulous.

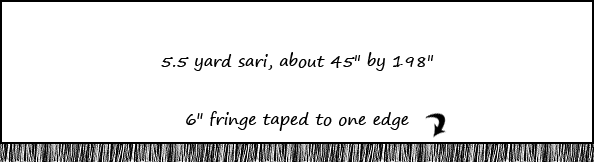

How to wear the sari as a Mesopotamian tunic: First use some Res-Q tape to attach fringe along one edge of your sari. (If you don’t have a sari, a 5-yard length of fabric right off the bolt would also work.) You should end up with a piece that looks like this:

To wear it, start by winding it around you at waist level, like a wraparound skirt. A belt or a string tied around your waist can be useful to keep it in place; you might also want to use a couple of safety pins. Then continue winding it around you upwards, as many times as necessary, and finish by throwing the last several feet of fabric over your shoulder.

More info: You can read more about the ancient Sumerian kaunakes on our Enheduanna costume page. There’s more discussion of the mythological angle in our Costume Candidate for 2013: Inanna-Ishtar blog post.

Main illustration credits: The Ishtar cylinder seal dated ca. 2200 BCE is in the collection of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago (see their Highlights of the Collection page). The Ishtar relief dated ca. 2000 BCE was recovered from Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), and is in the Louvre. The Mari statue is a modern copy of a life-sized sculpture found in Syria and dated to about 1800 BCE. It’s often called the “goddess with vase,” and may or may not represent Ishtar; nevertheless, the headdress and clothing are very similar to Ishtar’s attire. The illustration of the Neo-Babylonian court is by Roger Payne, and was created for Look and Learn magazine (no. 1044, dated 13 March 1982). The background painting is an artist’s recreation of the Ishtar Gate as it might have looked when new; the artist’s name is unknown.

The Queen of Sheba (ca. 950 BCE?) is claimed by both Ethiopia and Yemen. It’s not impossible that both are right; the ancient realm of Saba (Sheba) may have spanned the Red Sea. Or perhaps she was really the Queen of Meroë, and the name “Sheba” referred to something else entirely. The chronology is also rather difficult…but then again, maybe all this is beside the point. The Queen of Sheba is simply one of the great legendary figures of all time. For Ethiopians, who know her as Makeda, she is the mother of the nation and founder of a dynasty. For readers of the Bible and the Koran, she is the embodiment of opulence, wisdom, beauty, and mystery.

Given the uncertainty about exactly where and when the Queen of Sheba lived, depictions of her are all over the map. The paintings we’ve grouped in our main illustration above show the particular blend we’re going for with our costume: Ethiopian style gown, Egyptian necklace, Near Eastern veil, long waist sash (everybody was wearing those in the 10th century BCE), and an anachronistic crown. And a fan! For some reason the Queen of Sheba always has a fan. We chose peacock feathers to echo the Biblical reference to Solomon’s riches, though it’s probably another anachronism. But hey, it’s a Halloween costume, not a doctoral dissertation. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. White dress from Lotustraders. Since time immemorial, the basic Ethiopian dress has been a white caftan-like gown. This ingenious design from Lotustraders has drawstrings at the waist, sleeves, and hemline to give you a perfectly customized fit.

1. White dress from Lotustraders. Since time immemorial, the basic Ethiopian dress has been a white caftan-like gown. This ingenious design from Lotustraders has drawstrings at the waist, sleeves, and hemline to give you a perfectly customized fit.

2. Three chiffon veils: white, violet, and olive green. Each veil is 45 by 90 inches. Use the violet and green ones to knot around your waist as an ancient-style sash. The white veil goes over your head and under your crown.

3. Gold crown. It’s an anachronism, but big gold crowns are very common in depictions of the Queen of Sheba. We chose a somewhat-better-quality costume crown to live up to the rest of the outfit. The filigree work on this one features peacocks, which is a nice echo of the fan.

4. Egyptian collar-style beaded necklace. We think the Queen of Sheba should have at least one truly spectacular piece of jewelry, and this necklace fills the bill. It also reflects the Egyptian influence that would have been present in the Upper Nile. This necklace is actually from Egypt, so note the shipping time.

5. Peacock feather fan. This is a beautiful natural feather fan, especially considering the size: 27 inches wide and about 15 inches long. Very glamorous, and the peacock colors look wonderful with the Egyptian necklace.

6. Bracelets from Firemountain Gems. Firemountain sells to everyone at wholesale prices, so it’s a great place to stock up on inexpensive jewelry. We chose (clockwise from top left in the composite image): a set of three stretch bracelets with glass beads, a brass bangle, a set of goldtone bangles with blue beads, and another set of bangles with green faux jewels.

Gold, gold, and more gold: According to the Bible, the Queen of Sheba gave King Solomon “a hundred and twenty talents of gold, and a very great quantity of spices, and precious stones…” A hundred and twenty talents would have been about four tons. Four tons of gold! So lay it on. Put gold beads in your hair, wear gold sandals, pile on the rings. You’re the Queen of Sheba!

Persephone was a pre-Greek goddess who got drafted into the Olympic pantheon along with her mother Demeter. It’s a fair bet that she was the Queen of the Underworld long before the Greeks, with their usual penchant for male supremacy, added Hades to the mix and changed the story around. The Greek version is of course familiar: Persephone is the daughter of Demeter, the earth mother. While picking poppies one day in a field, she is abducted by Hades, who brings her to the Underworld to be his wife. During her absence Demeter becomes so distraught that the earth withers and all the plants die: wintertime. Only when Persephone is restored to her mother do the plants grow and bloom again. But because she had eaten some pomegranate seeds while in the Underworld, she is doomed to spend several months there every year.

For the costume, we’re going with the Queen of the Underworld aspect of Persephone. It is Halloween, after all. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

For the costume, we’re going with the Queen of the Underworld aspect of Persephone. It is Halloween, after all. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Black satin flat sheet. This is for your tunic. The Greeks wore simple draped tunics of dyed wool, a look which is easily replicated with sheets and safety pins. We give you instructions below on how to pin it together. A full size sheet will work for most people.

2. Black chiffon veil. The veil is 45 by 90 inches; drape it over your head and secure with the poppy wreath you’re going to make (next).

3. Red silk poppies. Get a few artificial poppies with wire stems and twist them together into a circlet. You can get a few extra to mix with your bouquet (#5).

4. Red and black stone flower necklace. Based on the emails and photos people have sent us, we think this necklace sold out because everybody bought it for their Persephone costumes!

5. Dead flower bouquet with skulls. Skulls! Can’t get more Underworldly than that. Mix it with a few artificial poppy stems for a vivid and very weird bouquet. If the skull bouquet is out of stock, you can easily make your own. Just get a dozen black roses ($7) and a pack of 1-inch black skull beads ($4). Use straight pins or glue to wedge a skull into the center of each rose. Voilà! Your own skull bouquet, even better than the one from the costume store.

Shoes: Simple leather sandals are best. Gladiators, thongs, something like that.

How to make the tunic: The simplest ancient tunic for costuming purposes is the Doric chiton, which consists of a single rectangle of fabric folded around the body. All you need is a flat sheet, some safety pins, and a belt or cord. Here are your chiton instructions:

Illustration credits: The central painting in our main illustration is Death the Bride by Thomas Cooper Gotch. The painting on the right is Proserpine by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

To the English, she was Grace O’Malley (1530-1603), notorious pirate. To the Irish, she was Gráinne Ní Mháille, Queen of Clew Bay, and her crews were just collecting taxes from the ships that entered her waters. True, these “taxes” were collected at the point of a sword by armed boarding parties of sailors who behaved an awful lot like pirates, but hey, a queen’s gotta do what a queen’s gotta do. Especially when her country is being invaded and colonized by a foreign power, which is exactly what was happening.

The backdrop to Grace O’Malley’s piracy was the ongoing English conquest of Ireland. Traditional clan chieftains like Grace were being pushed to the edge, their power under constant attack from the English overlords. The most famous incident in Grace’s life—her meeting with Elizabeth I—was a direct result of this persecution. When the English governor took Grace’s son captive, Grace boldly sailed to England to petition Elizabeth for his release. The amazing thing is that she succeeded. Elizabeth seems to have taken a liking to the Irish woman, perhaps sensing in her a kindred spirit. She promptly wrote to the governor in Ireland, instructing him to release Grace’s son and to henceforth treat Grace O’Malley as a friend of the crown.

We have a reasonably good idea of what an authentic 16th century Irish costume would look like; unfortunately, it’s impossible to find ready-made. Every single outfit we’ve seen has been a custom creation, usually commissioned by serious reenactment enthusiasts. For our purposes, we’re just going to make do with garments that are approximately the right shape and style. The items we suggest, from left to right:

1. Yellow chemise. The Irish chemise, or leine, was the basic national garment. By the 16th century it was dyed saffron and had big baggy sleeves—a style the English thought looked absolutely horrible. That probably made the Irish love it even more. This reenactment chemise in mustard yellow is the closest thing we can find ready-made.

1. Yellow chemise. The Irish chemise, or leine, was the basic national garment. By the 16th century it was dyed saffron and had big baggy sleeves—a style the English thought looked absolutely horrible. That probably made the Irish love it even more. This reenactment chemise in mustard yellow is the closest thing we can find ready-made.

2. Fair Maiden Dress in green. The fashion in Ireland was for a gown with a full pleated skirt, a loosely laced bodice, and peculiar open sleeves that allowed the sleeves of the leine to hang through. The Shinrone gown (historic pattern here) is the key piece of archaeological evidence for the period; we include a drawing of it in our main illustration. You can’t find a dress like that for sale, so we’re substituting this Ren Faire gown. The main thing it’s missing is the sleeves. It’s workable, though; just make sure you pin the skirt closed all the way down. A boatload of safety pins will do the trick.

3. Wool throw in muted Stewart tartan to use as a cloak. The Irish cloak, or brat, was a thick wool rectangle or semi-circle edged in heavy fringe. We chose plaid because it’s pretty, but checks, stripes, or solids would also be appropriate. (Don’t worry about the fact that this pattern is named after the Stewarts. Gaels and other Celts have been enjoying plaid since the Iron Age, long before the 19th century fad for assigning particular tartans to Scottish clans.) If you don’t have a nice wool throw you can use, just get a couple of yards of inexpensive fleece fabric in a plaid pattern (like this). You could even attach some contrasting fringe to the edge, since the Irish fashion was to beef up the fringe until it almost looked like a fur edging.

4. Penannular brooch. To fasten your cloak at the neck. The one we show is the large 3-inch size, listed at the bottom of the page.

5. Double wrap belt. To hold your sword, naturally.

6. Synthetic broadsword. It’s molded polypropylene, so you won’t do any damage with this thing. But it looks nice.

Shoes: Wear flat leather boots or booties. Nothing fancy; no bucket boots à la Pirates of the Caribbean. Wrong century.

Illustration credits: The drawing of the Shinrone gown is from the pattern by Kass McGann. The statue of Grace O’Malley is by the artist Michael Cooper, and stands on the grounds of Westport House, the County Mayo home of Grace’s descendants. The illustration of Grace O’Malley meeting Queen Elizabeth I is from the frontispiece of the Anthologia Hibernica, published in 1793. The small round portrait is from the cover of the children’s edition of Granuaile: Sea Queen of Ireland, written by Anne Chambers and illustrated by Deirdre O’Neill.

The pop culture image of Jezebel bears almost no resemblance to the woman who was queen of Israel in the 9th century BCE. There is nothing remotely sexy about Jezebel in the Bible; she’s just mean. By the same token, the biblical account was written by people who utterly loathed Jezebel and everything she stood for (Baal, Astarte, foreigners, uppity women), so it’s not exactly a balanced perspective. Can the real Queen Jezebel be recovered?

Probably not. It has been three thousand years, after all. What we can do—since this is a costume project—is think about what Jezebel might have worn. We know that she was a princess of Phoenicia by birth; we know that her marriage to King Ahab put her at the center of Israel’s wealthiest dynasty; we think it’s possible that she served as a priestess of Astarte; and we have a pretty good idea of what kings, queens, and priests in that part of the world were wearing in the 9th century BCE. Our costume is heavy on red and purple, since the Phoenicians were famous for their purple dye (which actually included a range of hues from bright crimson to blackish magenta). The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Full-length white chemise. Jezebel would have worn a fine-quality linen tunic as her underdress. That this is a Ren Faire costume item shouldn’t surprise, since the medieval chemise is a direct descendant of the ancient Near Eastern sleeved tunic.

1. Full-length white chemise. Jezebel would have worn a fine-quality linen tunic as her underdress. That this is a Ren Faire costume item shouldn’t surprise, since the medieval chemise is a direct descendant of the ancient Near Eastern sleeved tunic.

2. Red embroidered galabeya plus gold fringe. Our galabeya originally came from eBay; there is an ever-changing selection of patterns and styles offered by various sellers. (One store that often has similar galabeyas is EgyptMart.) The only thing you’ll need to add is fringe. Fringes were extremely important in Jezebel’s day; all VIPs had elaborate fringes on their garments, and in fact fringes became items of ritual significance in Judaism. Get two yards of gold fringe (you’ll have some left over) and attach it to the hem of the dress with double-sided tape.

3. Purple fringed hip scarf. More fringe, and a great shot of purple.

4. Purple lurex veil. More purple, plus gold threads. Drape over your head and secure with the crown (next).

5. Red fez adorned with a gold necklace. It was the Age of Coneheads: everybody who was anybody was wearing some kind of big domed or pointed thing on their heads. A fez is a reasonable approximation of the female headdress of the day. Remove the tassel and wrap the necklace around the fez to dress it up.

6. Glass bead choker and earring set. Another thing the Phoenicians were famous for was their glass, including beads. They loved Egyptian jewelry designs, which they executed in glass and ceramic rather than precious stones. Phoenician women are also described as wearing dog-collar chokers and multiple strands of beads.

Additional jewelry: The Phoenicians belonged to the “more is more” school of personal adornment. Gold and glass beads were their specialty, and they liked to wear as many of them as humanly possible. Pile on any bracelets you have; wear multiple earrings if you have the piercings (the Phoenicians pierced their ear rims as well as lobes); and wear a ring on every finger.

Makeup: When Jezebel knew that she was about to be killed by rebels, she “painted her eyes and adorned her head and looked out the window.” It seems obvious that she was going to meet her death arrayed as a queen, and possibly as a priestess of Astarte (the “woman at the window” motif is thought to represent the goddess). The eye paint was probably the kohl that was used in the Near East and Egypt to outline the eyes. Get some eyeliner and lay it on thick, top and bottom.

Shoes: Gold sandals would be ideal, but any kind of simple flat sandal will work.

Why yes, that is a snake on her head. Ixchel is the Maya goddess of fertility, childbirth, weaving, and maybe the moon. The snake in her hair is the cosmic serpent, representing rain and the creative principle, while Ixchel herself is shown pouring out the waters of heaven from an upturned jar. She wears a blue sarong wrapped around her waist (sometimes patterned with stars, sometimes with crossbones), a bandeau blouse, and a necklace of big jade beads. She’s also a jaguar goddess, and sometimes sports jaguar claws and pelt. Occasionally she’s even depicted as a death-dealing warrior, which is a neat complement to her more familiar role as midwife. Ixchel’s got both ends of the life cycle covered.

Nowadays Ixchel is popularly assumed to be a moon goddess, but it’s not clear if that’s how the ancient Maya saw her. It’s quite possible that the modern association with the moon is the result of a 20th century mix-up; see Mending the past: Ix Chel and the invention of a modern pop goddess. There are images in the Mayan codices of a young moon goddess sitting in the lunar crescent, holding a rabbit. Is this a youthful version of Ixchel, or a completely different figure? We don’t know, but it’s interesting that this young goddess also wears a snaky headdress.

Nowadays Ixchel is popularly assumed to be a moon goddess, but it’s not clear if that’s how the ancient Maya saw her. It’s quite possible that the modern association with the moon is the result of a 20th century mix-up; see Mending the past: Ix Chel and the invention of a modern pop goddess. There are images in the Mayan codices of a young moon goddess sitting in the lunar crescent, holding a rabbit. Is this a youthful version of Ixchel, or a completely different figure? We don’t know, but it’s interesting that this young goddess also wears a snaky headdress.

The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Sequined embroidered sarong in blue. This is for your skirt. The color is wonderfully vivid—reminiscent of the famous “Maya Blue” paint that coated figurines of Ixchel—and the sequins evoke the stars that were sometimes embroidered on her skirt.

2. Blue half-sarong. Use this as your top; just tie it around you bandeau style.

3. One yard of faux jaguar fur fabric. Okay, really it’s faux leopard fur, but close enough. This fabric is 62 inches wide, so if you buy one yard you’ll have a big 36 x 62 inch rectangle. That should be enough to wrap around your hips as a sash, minus a few scraps you’ll need to snip off to use on your collar (#6).

4. Jewelry. Ixchel wears a distinctive necklace of big green jade beads. Assuming you don’t have any priceless jade jewelry on hand, this green bead necklace is a good substitute. Instead of giant ear spools, we chose blue tassel earrings—reminiscent of sheets of rain cascading down. Complete your look with a cuff bracelet.

5. Headdress. This is just a couple of fair trade Guatemalan cotton scarves tied around your head (Ixchel is also the goddess of weaving!), with a cute plush snake toy tucked inside. We chose scarves in purplish blue and light greenish blue. You can get a plush snake online, or just go to the grocery store and look in the pet aisle for dog toys. Arrange it so that the head of the snake kind of pokes out over the top of the scarves. Accentuate the ensemble with this glass red snake from Firemountain Gems; just tie it on to the front of your headdress with thread.

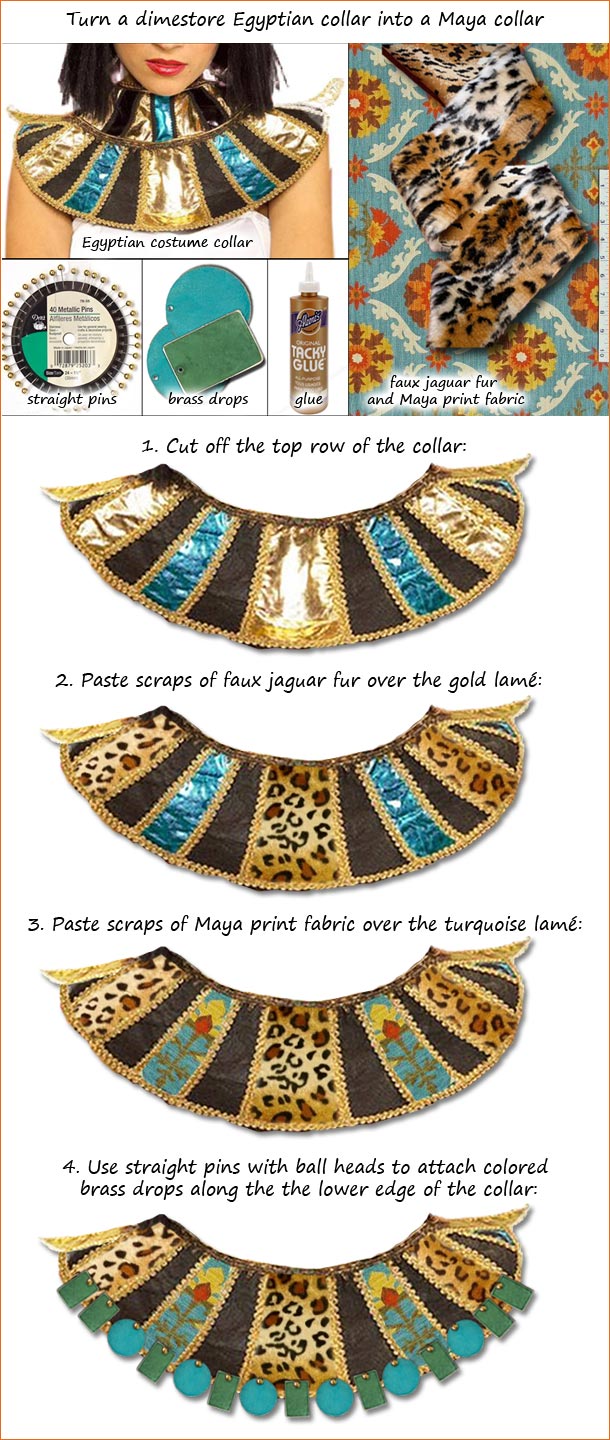

6. Collar. Here’s a costumer’s trick: if you need to make a Maya costume on the cheap, you can start by cannibalizing some dimestore Egyptian stuff. The basic shapes are very similar. Here’s what you need:

- Egyptian collar

- Faux jaguar fur (use scraps left over from your hip wrap)

- Maya print fabric (you just need scraps, so you can get by with a sample swatch)

- Two packs of green brass drops

- One pack of teal brass drops

- Gold-tone straight pins with ball heads

- Fabric glue

Hair: If at all possible, pull your hair up into a big ponytail right on top of your head. A topknot would also work. You want to create a vertical line, since the Maya concept of beauty involved having a head that looked as much like an ear of corn as possible. You can accentuate your ponytail/topknot with some colored feathers.

What to carry: Ix Chel is shown pouring out the waters of life from her magical jar, so you could carry an earthenware-looking pot with you, perhaps filled with Halloween candy. The jar we show in our illustration is a real terra cotta vase from Mexico, which is gorgeous but probably much too heavy to actually haul around with you on Halloween. (It would look great in your house though.) We suggest you go to the local home & garden center and look for a lightweight resin pot that’s molded to look like earthenware.

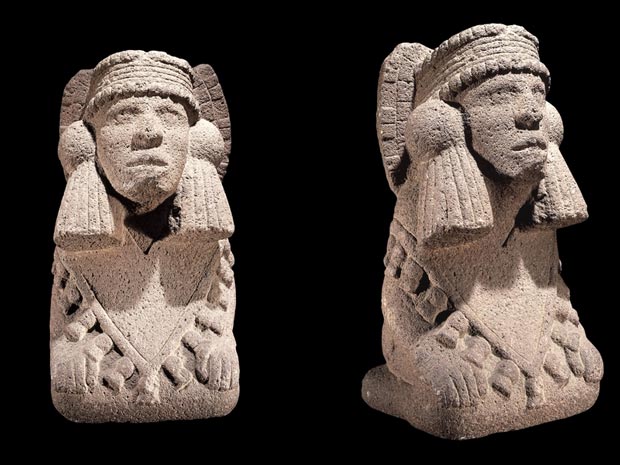

Illustration credits: The drawing of Ixchel pouring water from her jar is on page 39 of the Dresden Codex. The drawing of the young goddess (young Ixchel?) offering a plate of fish is on page 23 of the Dresden Codex. The warrior goddess figurine is from Jaina Island, and is identifed in The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya by Mary Miller and Karl Taube. The round painting of the Maya cosmos is An illustration of the Maya universe on a tiered pyramid by Ken Dallison for National Geographic; notice that the young moon goddess is sitting in the lunar crescent in the upper left portion of the sky. The background image is an old painting of life in Chichen Itza, artist unknown.

Chalchiuhtlicue, whose name means “She of the Jade Skirt,” is the Aztec goddess of rivers, lakes, seas, springs, and all running water. She is traditionally depicted as an elegant woman in blue-green clothes, with her skirt flowing out to form the river of life—and of death, for Chalchiuhtlicue also presided over the fourth sun of creation, which was destroyed by flood. She wears a quechquemitl (a poncho-like garment with the point in the front) and a magnificent feather crown. Our costume design involves some very easy crafting—a few straight pins and some double-sided tape—but no sewing. You’ll need about three yards of Aztec pattern ribbon for the headdress, feather cuffs, and poncho top.

The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Feather headdress. Attach a length of Aztec pattern ribbon around the gold braid trim; you can use straight pins so as not to mess up the feathers. Finish it off with turquoise chandelier earrings, which can just hook onto the braid trim on each side of the headdress.

2. Black poncho top. The top we used isn’t available anymore, but pretty much any plain black poncho will work (this one, for example); you’re going to temporarily enhance it with ribbon and fringe in a V-shape, which will help give the effect of a quechquemitl. You’ll need two yards of the Aztec pattern ribbon and two yards of coordinating tassel fringe. Arrange the ribbon and fringe in a deep double-V-shape, with points in the front and the back, and attach with Res-Q tape or even just safety pins. If you get ambitious, you can also trim the edges of the poncho with fringe; you would probably need at least four yards for that. (If you want to make a quechquemitl from scratch instead of buying a poncho, Mexicolore has good instructions.)

3. The all-important jade skirt! Any maxi skirt in that color range will do.

4. Blue-green statement necklace. The one we used is made out of shell, but is no longer available.

5. Feather cuffs. One yard of feather trim will be more than enough to do both cuffs. Attach the Aztec pattern ribbon to the base of the feather trim with double-sided tape, then wrap the assembled cuff around your wrist. You can safety-pin the ends in place.

6. Turquoise gladiator sandals. Aztec shoes vaguely resembled ankle-high gladiator sandals. If you don’t already have gladiators, these would be perfect.

Hair: If you want to try to do your hair like Chalchiuhtlicue, this sculpture in the British Museum shows you what you need to know. Basically we’re looking at two big fluffy pigtails/ponytails, one on each side of the head:

Costume illustration credits: In the upper right corner of our main illustration is Sandra M. Stanton’s wonderful oil of a resplendent Chalchiuhtlicue in feather headdress. The luminous center painting is by ladycat17 on deviantART. The insets are images of Chalchiuhtlicue from the Aztec codices.

“If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” Did Emma Goldman (1869-1940) really say that? In a word, no. The sentiment was certainly hers, and in her memoirs she told of being admonished for dancing when she was a young radical; but the actual words? No. The quote (or rather, misquote) is best thought of as a paraphrase of Emma’s philosophy.

She certainly did love to dance. She loved life, period: food, wine, books, music, romance. “Red Emma” was the most famous anarchist in America, notorious for her stances on everything from labor unions to free love. But despite the scurrilous stories spread by her opponents, Emma’s anarchy had nothing to do with throwing bombs. What she believed in was freedom. She wanted people to be free from oppression, whether that oppression was economic or religious or social. It’s no wonder she’s been adopted as the patron saint of so many liberation movements over the past half-century.

For our costume, we decided to go with the most famous photograph of Emma, the one that’s on all the T-shirts (center above). She’s wearing a black blouse or dress with a square neck, a lighter color hat, and pince-nez glasses. The pince-nez were a constant, and probably the one thing you must have if you want to dress up like Emma. Though her look evolved over time, she never seems to have changed her choice of eyewear. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

For our costume, we decided to go with the most famous photograph of Emma, the one that’s on all the T-shirts (center above). She’s wearing a black blouse or dress with a square neck, a lighter color hat, and pince-nez glasses. The pince-nez were a constant, and probably the one thing you must have if you want to dress up like Emma. Though her look evolved over time, she never seems to have changed her choice of eyewear. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Evangeline blouse in black. The external lacing on this blouse makes it completely inauthentic, but it does have a nice shape. A more conservative option is the Lenora blouse.

2. Gibson Girl skirt in black moire. This is a full-length skirt, despite the way it looks in the picture. An extremely similar but less expensive skirt is available here.

3. Corduroy and satin hat in tan. The shape of this hat looks a lot like the one Emma wore; we suggest dressing it up with a scarf and cockade (next).

4. Red print scarf and red cockade. Wrap the scarf around the crown and tuck it behind the fabric leaves of the hat. Add a red cockade (which nowadays we usually call a “rosette”) for revolutionary flair. Just cut off the end ribbons so it won’t look like you’ve won a prize. Although black is the color associated with anarchists now, back in Emma’s day the more typical color was red. Revolutionaries would sometimes wear a cockade in their hats or on their lapels to show their allegiance.

5. Pince-nez glasses. The all-important pince-nez!

6. Victorian lace-up boots.

Cigar: Emma smoked cigars, which we do not recommend (evil addiction! run away, run away!). But if you do smoke, or if you just want to carry a prop and be in character, get a cigar.

Blintzes: If you’re going to the kind of party where people bring food, we suggest blintzes. Seriously. Emma was a great cook, and blintzes were her specialty. Cherry blintzes, perhaps?

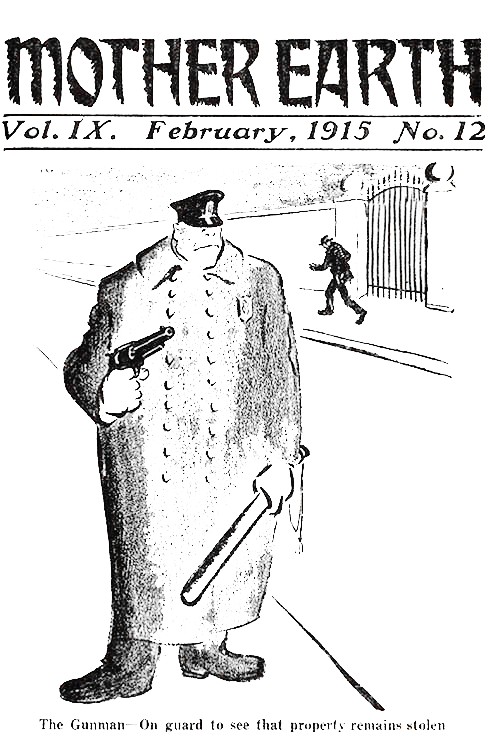

Extra credit: We’ve taken the front cover of the February 1915 issue of Mother Earth, Emma’s anarchist journal, and rendered it as transparent png file. You could print off a bunch of copies on whatever color paper you like, and pass it out to your friends. If you’re handy with any kind of graphics software, you could also modify it to include your own images or message. We’ve scaled it to fit on a letter-size sheet:

Mama Quilla is the Inca goddess of the moon. Married to Inti, the sun god, she is the female half of the divine equation. Before the Spaniards got to work smashing and melting things, Mama Quilla was worshipped in temples with walls of pure silver. Silver is her metal: in Inca mythology, silver is the “rain of the moon” (or tears of the moon), just as gold is the sweat of the sun.

Dressing up as Mama Quilla is an exercise in creativity, since it seems her original cult image was just a silver disk. We’re thinking of something a little more human. For the costume, we’re taking our cue from the moon maidens at the annual Inca Festival of the Sun in Cusco; they wear white dresses with embroidered symbols, blue cloaks, and silver arm cuffs. We’re also inspired by the silver votive figurines that have been recovered from Inca graves. These little figurines are dressed in complete miniature outfits, including feather headdresses.

Dressing up as Mama Quilla is an exercise in creativity, since it seems her original cult image was just a silver disk. We’re thinking of something a little more human. For the costume, we’re taking our cue from the moon maidens at the annual Inca Festival of the Sun in Cusco; they wear white dresses with embroidered symbols, blue cloaks, and silver arm cuffs. We’re also inspired by the silver votive figurines that have been recovered from Inca graves. These little figurines are dressed in complete miniature outfits, including feather headdresses.

The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. White layered dress. LotusTraders makes a ton of long white dresses, but we especially love the floaty tiered layers on this one.

2. Royal blue ruana. There is surely no garment more graceful than a ruana.

3. Woven textile from Ecuador. This multipurpose textile is 20″ x 60″ and features traditional Andean patterns. Just fold it lengthwise and wrap it around your waist as a sash. These come in different colors; we chose the light blue, which has all the same colors as the moon maiden outfits.

4. White feather headdress. When we found this item we were thrilled. White feathers plus silver sequins.

5. Hammered silver disk necklace and earring set. A perfect echo of Mama Quilla’s original cult image. Hang the earrings from each side of the feather headdress.

6. Silver metallic foil board for DIY arm cuffs. Save a ton of money and make your own silver cuffs from foil craft board. A single 10×13 inch sheet will make two cuffs (each cuff 5×13 inches). Just roll the strips around your wrist and have a friend help you tape the ends together.

Shoes: The skirt is long and full, so your shoes won’t show much. But we suggest something silver (of course).

Illustration credits: The main photo in our illustration is from the annual Festival of the Sun in Cusco, Peru. The silver disk (inset image) is from the Chimor kingdom on the north coast of Peru; it was made sometime between 1000 and 1400 CE, before the rise of the Inca Empire. The silver votive figurine (inset image) is from an Inca burial.

You would think that the person who discovered nuclear fission would be one of the most famous scientists of the 20th century. You would think she’d be a household name. But unless you’re a geek or a history buff, it’s possible that you’ve never even heard of Lise Meitner (1878-1968).

Meitner was born in Austria at a time when women were barred from universities and even sending girls to high school was a shocking novelty. Yet she overcame a lifetime of legal and social barriers to become one of the top nuclear physicists in the world. In the 1930s she set up a team in Berlin to explore transuranium elements, recruiting Otto Hahn to do the chemistry experiments. Anti-Semitism intervened in the form of the Nazis, and Meitner, born a Jew, was forced to flee Germany in 1938. From her exile in Sweden she continued to direct the experiments in Berlin, communicating with Hahn by letter and even meeting with him secretly in Copenhagen. The result was one of the great breakthroughs in the history of physics. On Christmas Day 1938, in a huge rush of insight while mulling over the data from Berlin, Meitner suddenly Saw It All: that the atom could be split, that the resulting energy was described by Einstein’s E = mc², that nuclear theory itself had to be fundamentally revised.

Hahn published the fission results without listing Meitner as co-author, a move that was perhaps understandable given the Nazi situation. But what happened next was not: in 1944 Otto Hahn alone was awarded the Nobel Prize for discovering nuclear fission. Meitner got bupkis. The Nobel committee simply ignored her existence. And so it is that Lise Meitner is often called the greatest scientist to never win a Nobel prize.

But on to the costume! We’re going with the charming Gibson Girlish photo of Lise as a young doctoral student in Vienna in 1906 (center of our main illustration). We don’t know what she really had on the end of that cord around her neck (a pocket watch?), but we decided it would be fun to imagine it was her slide rule. If your physics lab is having a Halloween party, you will be the belle of the ball. Total geek heaven. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Gibson Girl skirt in black moire.

2. Pinstripe blouse in black and white.

3. Black velvet belt.

4. Straw boater.

5. Wrist length satin gloves in white. Lise would have worn kid gloves, but these are a much less expensive alternative.

6. Slide rule on a 40″ loupe chain. Both from eBay (purchased separately). The traditional slide rule had a belt loop on the leather case so you could carry it with you everywhere. A loupe chain is perfect for hooking onto that belt loop. The real trick is finding a slide rule, much less one with a leather case.

Optional corset: It’s not required, but a corset will definitely help give you the correct period silhouette.

Shoes: Victorian lace-up boots. These also have a sneaky zipper on the inner side so that you don’t have to fool with the laces if you don’t want to:

We don’t know her name. And unless somebody deciphers Linear A, we probably never will. All we know is that she existed, and that her world was beautiful. The centerpiece of our main illustration is an artist’s recreation of life in the queen’s apartments at the Palace of Knossos around 1500 BCE (bottom center). Note, however, that we’ve had to modify it to make it G-rated, since the ladies of the Minoan civilization apparently wore their bodices completely open.

Minoan clothing was astonishing. There was nothing else remotely like it in the ancient world. If the paintings from Crete are accurate, the women wore multicolored flounced skirts, tightly fitted bodices, and gorgeous fabrics with stripes and dots and spirals. (The men wore loincloths. Heh.) Our costume design attempts to recreate this look with modern garments, and without getting you arrested for indecent exposure. The trickiest part is the bodice: our solution is to combine a corset with a bolero jacket, trimmed with Minoan-looking spiral pattern ribbon. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Full length tiered skirt in red. This beautiful skirt has tiered flounces, just like the Minoan paintings. (The tiers have contrasting tones, though the large product image of the green skirt kind of washes out the difference.)

1. Full length tiered skirt in red. This beautiful skirt has tiered flounces, just like the Minoan paintings. (The tiers have contrasting tones, though the large product image of the green skirt kind of washes out the difference.)

2. Purple corset trimmed with spiral pattern ribbon. Use a double-sided tape like Res-Q to temporarily attach the ribbon to the corset; it won’t leave any residue. You’ll need three or four yards of the ribbon to trim the top and bottom of the corset, as well as to run trim vertically alongside the front fastenings.

3. Satin bolero jacket in eggplant trimmed with spiral pattern ribbon. You’ll need another three or four yards of the ribbon for trim; again, use the Res-Q tape to temporarily attach it. The arms on this jacket come unhemmed, so you can fold them up to elbow height. When you put on the jacket, use a couple of pins to attach it to the corset to help create the look of one garment.

4. Three yards of cord in cayenne red. This is for your belt; wrap it around your waist about three times. Minoan belts had a peculiar rolled shape, so what we want is the thickest cording we can find. This is 3/8 inch, but you may be able to find a larger size. You might also want to just cannibalize some drapery tiebacks for the purpose.

5. A “Greek goddess” wig (from a costume store) with gold beads and gold metallic ribbon. Minoan hairstyles were very elaborate, as you can see from the illustrations. Unless you can do that with your own hair, a wig like this is probably the best bet. It’s actually easier to work with a wig, since you can set it in front of you while you attach the beads and ribbon. We used the gold beads to wrap the crown of the wig as well as the bangs line, and then ran vertical rows between them. The metallic ribbon encircles the wig at the bangs line. Bobby pins are your friend.

6. Jewelry from Firemountain Gems. Firemountain sells to everyone at wholesale prices, so it’s a great place to stock up on jewelry. Our selections pay homage to the patterns and materials beloved by the Minoans. Clockwise from top left in the composite image: a glass bead necklace; a cuff bracelet; a set of 10 mixed bead bracelets; and a pair of gold-and-rhodium earrings with a Greek key design (related to the Minoan meander).

Shoes: Minoan footwear was interesting. Indoors people usually went barefoot, but outside they wore shoes. Crete is a rocky place, and the inhabitants favored closed-toe shoes and boots. Some of the paintings show Minoans wearing calf-high and ankle-high boots; others depict low shoes combined with what looks for all the world like athletic socks. We decided that purple boots would look good with our queen costume. The Cookie boots by Story come in a beautiful rich purple:

Illustration credits: The artist’s reconstruction of life at the Palace of Knossos appeared in The Epic of Man, by the Editors of LIFE Magazine, 1961. The artist’s name is unknown. The other images are of Minoan frescoes found at the palace.