Thanks to our Kickstarter campaign for 2013, we’re adding 19 new costumes this season, 7 of which our backers and supporters will get to vote on. This series of posts is designed to briefly introduce the many notable women and legendary figures we’ll be considering. Voting will take place spring/summer of 2013.

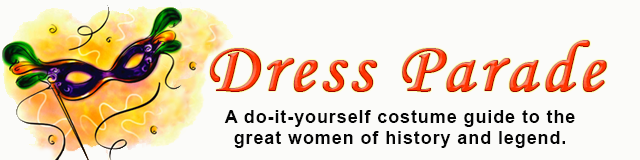

Elizabeth I is so famous that people often ask us why we don’t already have a costume for her. Honest answer: because it’s hard. I mean, look at those clothes. Not exactly a candidate for our “costumes you can make from a bedsheet” series, is what I’m saying.

But of course Elizabeth was a great queen—one of the greatest queens in history. Daughter of Anne Boleyn and noted serial killer Henry VIII, Elizabeth proved everybody wrong about the ability of women to rule. For over 45 years she steered England with a sure hand, leading it from a nightmare of fear and dissent to a Golden Age of literature and exploration. She ought to be represented, no question. If only she’d worn a chiton…

Think we should add an Elizabeth I costume to Take Back Halloween? If you missed our Kickstarter campaign you can still become a supporter and get to vote on the new costumes.

Thanks to our Kickstarter campaign for 2013, we’re adding 19 new costumes this season, 7 of which our backers and supporters will get to vote on. This series of posts is designed to briefly introduce the many notable women and legendary figures we’ll be considering. Voting will take place spring/summer of 2013.

When patriarchal religions collide with goddess-worshipping cultures, strange things happen. The female deities get demoted, tamed, domesticated. Divine Mothers are married off to father gods and transformed into jealous nags, awesome creator goddesses are turned into fertility nymphs, and sovereign queens are re-cast as trophy wives. That’s what happened when the migrating Greeks (patriarchal Indo-Europeans) arrived in the Balkans, and it’s what happened when their cousins, the Indo-Aryans, arrived in South Asia. It probably happened with other Indo-European tribes as well, but it’s clearest with the Greeks and the Indo-Aryans. The classical mythologies of both cultures are full of crash debris.

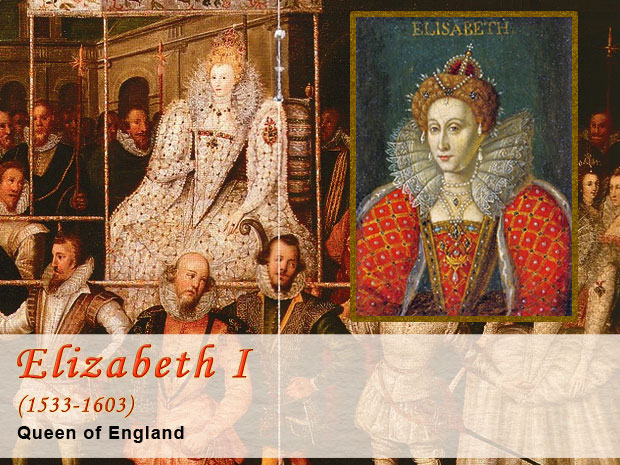

Queen Draupadi is a case in point. As the heroine of the Mahabharata, she’s practically the poster child for Formerly Independent Goddesses Trapped in Patriarchal Myths And Not Liking It One Bit. Her polyandrous marriage to the five Pandava brothers is surely a relic from a pre-patriarchal era, and her miraculous birth from a fire altar strongly hints that we’re dealing with an ex-goddess. But the Mahabharata insists on making her subordinate to her five husbands. The men treat her as shared chattel, and even gamble her away in a dice game. Draupadi protests vigorously, but the day is saved only when Krishna intervenes from heaven.

Three thousand years later, poetic justice has prevailed. Draupadi the Fire-Born has been reclaimed as a feminist icon, with the complexity of her story providing an almost endlessly rich source of contemplation for today’s women. It’s probably not what the authors of the Mahabharata had in mind, but we think Draupadi would be pleased.

Think we should add a Draupadi costume to Take Back Halloween? If you missed our Kickstarter campaign you can still become a supporter and get to vote on the new costumes.

Thanks to our Kickstarter campaign for 2013, we’re adding 19 new costumes this season, 7 of which our backers and supporters will get to vote on. This series of posts is designed to briefly introduce the many notable women and legendary figures we’ll be considering. Voting will take place spring/summer of 2013.

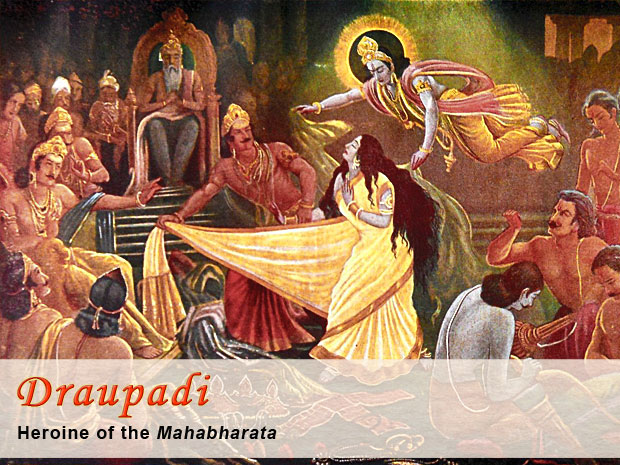

A couple of thousand years ago, Sudan was home to a remarkable civilization. The Kingdom of Meroë flourished from about 300 BCE to 300 CE, with its own writing system (not yet fully deciphered), an iron-working industry that was one of the engines of the ancient world, and trade contacts as far afield as Europe and India. An intriguing aspect of Meroitic culture was the ruling role played by queens, who were known by the title Kandake (traditionally spelled Candace). Amanishakheto was surely one of the greatest Kandakes; the treasure plundered from her pyramid in Naqa demonstrates the wealth and power at her command. She may have been the famous “one-eyed” Kandake who led a war against the Romans in the 20s BCE, successfully keeping Meroë out of Rome’s grasp even as Egypt and Lower Nubia were reduced to imperial provinces. (It also might have been her predecessor, Amanirenas, but until the Meroitic language is deciphered, we can’t be sure. The Greek historians only referred to the queen by her title, not her name, and the exact dating of each Kandake’s reign is iffy.)

The documentary Nubia: The Forgotten Kingdom has great footage of the Meroitic ruins and Amanishakheto’s jewelry, with actors recreating scenes from the life of the queen and of the creepy European fortune hunter who plundered and destroyed her pyramid in the nineteenth century:

Think we should add an Amanishakheto costume to Take Back Halloween? If you missed our Kickstarter campaign you can still become a supporter and get to vote on the new costumes.

If you’ve been following along you know that of the 19 new costumes we’re introducing this year, 7 are to be voted on by our Kickstarter backers and supporters. I think of those as the People’s Choice costumes. The way things are shaping up, we’re going to go ahead and try to get the voting done for the 7 People’s Choice costumes by the end of this month. That way we’ll be able to figure out the work plan for the season. We’ll resume publishing the little mini-bios in the Costume Candidates series so everybody knows who the nominees are, and then we’ll figure out how to run the poll.

To recap, here are the Costume Candidates we’ve published so far:

At the same time that we’re doing this, of course, progress is continuing in our secret workshop on the other costumes. We published Lasiren earlier this week, and we’re working on a second Special Request costume commissioned by another wonderfully generous Kickstarter backer. We’re also working on the 10 costumes already announced (Grace O’Malley, Anne Bonny and Mary Read, Zheng Yi Sao, Hypatia, Marie Curie, Grace Hopper, Rosalind Franklin, Queen Christina of Sweden, the Trung Sisters, and Amelia Earhart).

Isn’t she gorgeous? Lasiren (also spelled La Sirène) is the Haitian mermaid goddess of the sea. This is one of the two Special Request costumes from our Kickstarter campaign that we’ll be presenting this year. The wonderful backer who commissioned Lasiren prefers to remain anonymous, but thank you!

Isn’t she gorgeous? Lasiren (also spelled La Sirène) is the Haitian mermaid goddess of the sea. This is one of the two Special Request costumes from our Kickstarter campaign that we’ll be presenting this year. The wonderful backer who commissioned Lasiren prefers to remain anonymous, but thank you!

You can read all about Lasiren on her page. The costume isn’t difficult, but it does involve several components and a lot of craft paint. The level of complexity is about on par with our Freyja costume from last year. There’s no sewing, of course, but there is some pinning and gluing and painting. If you can work a safety pin and use a paint brush, you can make this costume.

Alternatively, if you have a readymade mermaid outfit that you’re happy with, you can certainly wear that instead. Just add a crown (because Lasiren is the queen of the sea) and ideally a golden horn of some kind. Even a glittery party horn would work, like the kind people blow at birthday parties and on New Year’s Eve. Drape on as much bling as you can—fake pearls, fake gold coins—to represent the sunken treasure that belongs to Lasiren, and voilà! You’re the mermaid queen!

P.S. Listen to the Haitian children’s song about Lasiren here.

Actually they were here a week ago; but within an hour of publishing the news to our Kickstarter backers on April 15, the Boston Marathon bombing happened. Buttons were the last thing on people’s minds.

But a horrible week has ended and it’s time to move forward, so: buttons! There are 63 buttons in all, one for each of our existing costumes. These are mini pinback buttons, 1.25″ across, great for wearing or collecting. Kickstarter backers at the $25 level get 5 buttons of their choice, and backers at the $50 level and above get 10 buttons. The designs are grouped by category:

Buttons – Glamour Grrls

Buttons – Goddesses and legends

Buttons – Notable Women

Buttons – Queens

Thanks to all our wonderful Kickstarter backers for supporting our project!

Every year on International Women’s Day, potted histories appear online to explain why March 8 is the day we honor women. Many of them are wrong.

Back in the 1980s historian Renée Coté undertook a meticulous search of the records, trying to figure out the origins of the March 8 date (see “International woman’s day: in search of the lost memory”). There were a number of women-led strikes and marches and protests in the years leading up to 1914, but none of them happened on March 8.

Back in the 1980s historian Renée Coté undertook a meticulous search of the records, trying to figure out the origins of the March 8 date (see “International woman’s day: in search of the lost memory”). There were a number of women-led strikes and marches and protests in the years leading up to 1914, but none of them happened on March 8.

The earliest Women’s Day observances were held on a variety of dates:

- May 3, 1908, in Chicago

- February 28, 1909, in New York

- February 27, 1910, in New York

- March 19, 1911 (the first real International Women’s Day) in Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland

In 1914 a Women’s Day observance was scheduled for March 8—probably because that was a Sunday and thus convenient for working women—and that’s the date that stuck. The German poster at right advertised the event.

(Here’s the English translation: “Give Us Women’s Suffrage. Women’s Day, March 8, 1914. Until now, prejudice and reactionary attitudes have denied full civic rights to women, who as workers, mothers, and citizens wholly fulfill their duty, who must pay their taxes to the state as well as the municipality. Fighting for this natural human right must be the firm, unwavering intention of every woman, every female worker. In this, no pause for rest, no respite is allowed. Come all, you women and girls, to the 9th public women’s assembly on Sunday, March 8, 1914, at 3pm.”)

Three years later, on March 8, 1917, International Women’s Day achieved world-shaking significance. On that date (which was February 23 in Russia, where they were still using the old Julian calendar), women in Saint Petersburg went on strike for “Bread and Peace.” They were demanding not only the vote but an end to the war and the food shortages that were crippling the nation. Their protest evolved into the first Russian Revolution.

Here in the United States, March 8 never really caught on as a big popular observance. (The fact that it was a major Soviet holiday may have played a tiny role there.) But it is the reason National Women’s History Month, which was established by Congress in 1987, is in March. Over on our Facebook page we’re celebrating all month with “this day in history” updates.

Useful Links

International Women’s Day (UN)

Women’s History Month (Library of Congress)

National Women’s History Project

MAKERS: Women Who Make America (PBS)

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) devoted her life to the cause of women’s suffrage, toiling for over 50 years in the face of incredible opposition (not to mention ridicule). As the de facto “Napoleon” of the 19th century women’s movement, she marshaled forces from all over the country into a huge national campaign. Sadly, she did not live to see victory: women didn’t get the vote until 14 years after her death.

For the costume, we’re going with her late-century look, since that’s most iconic. The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Late-Victorian dress. From the lace front and cuffs to the puffed sleeves, this dress is a great match for some of the most famous portraits of Susan B. Anthony. Don’t wear the bonnet that comes with it—instead do your hair up in a bun or wear a wig (#2). You’ll probably need a crinoline to help the skirt pouf out.

2. Grey wig. If your own hair isn’t grey or silver, this wig should do you up.

3. Round granny glasses.

4. Victorian lace-up boots.

5. Customizable sash. They might have these in your local party store. If so, you can get one and write “Votes for Women” on it.

Thanks to our Kickstarter campaign for 2013, we’re adding 19 new costumes this season, 7 of which our backers and supporters will get to vote on. This series of posts is designed to briefly introduce the many notable women and legendary figures we’ll be considering. Voting will take place spring/summer of 2013.

Most Americans learn in school that Juno is the Roman equivalent of the Greek goddess Hera: wife of the supreme god, patroness of marriage. The reality is more complex. The problem with understanding Juno (as well as Hera) is that Indo-European mythology has gotten tangled up with an earlier substrate of belief, creating a bit of a mess. An added difficulty is that Greek and Roman thinkers liked to normalize their respective deities into matchy-matchy pairs, even when the fit wasn’t particularly snug. As a result a great deal of indigenous complexity was lost. Nevertheless, it’s clear that Juno was far from merely Jupiter’s wife. She was extremely ancient and extremely important, and she may very well have been the original Creator Goddess. A hint of that peeks through in Aesop’s fable of Juno and the Peacock:

The peacock came to see Juno, because he could not accept with equanimity the fact that the goddess had not given him the song of the nightingale. The peacock complained that the nightingale’s song was wondrously beautiful to every ear, while he was laughed at by everyone as soon as he made the slightest sound.

Juno then consoled the peacock and said, “You are superior in beauty and superior in size; there is an emerald splendour that shines about your neck, and your tail is a fan filled with jewels and painted feathers.”

The peacock protested, “What is the point of this silent beauty, if I am defeated by the sound of my own voice?”

“Your lot in life has been assigned by the decision of the Fates,” said Juno. “You have been allotted beauty; the eagle, strength; the nightingale, harmony; the raven has been assigned prophetic signs, while unfavourable omens are assigned to the crow; and so each is content with his own particular gift.”

Do not strive for something that was not given to you, lest your disappointed expectations become mired in discontent.

Think we should add a Juno costume to Take Back Halloween? If you missed our Kickstarter campaign you can still become a supporter and get to vote on the new costumes.

Illustration credit: Juno and Her Birds (1887) by Walter Crane.

Thanks to our Kickstarter campaign for 2013, we’re adding 19 new costumes this season, 7 of which our backers and supporters will get to vote on. This series of posts is designed to briefly introduce the many notable women and legendary figures we’ll be considering. Voting will take place spring/summer of 2013.

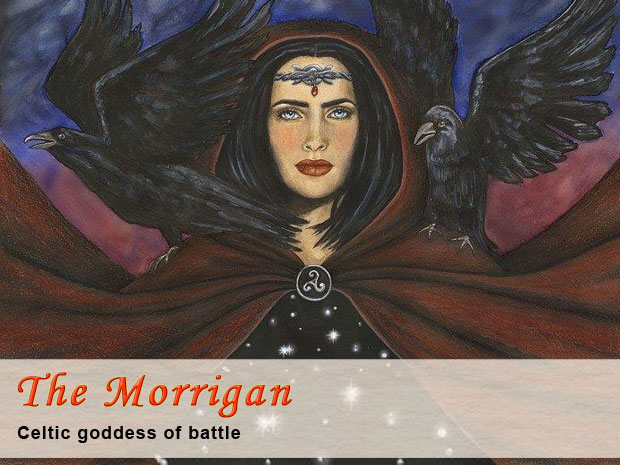

It’s clear from their mythologies that the prehistoric Celts and Germans spent many centuries living next to each other in Europe. Of course both groups are Indo-European, which accounts for quite a few shared concepts, but the similarities suggest an especially close relationship. The Morrigan, whose name means something like “Phantom Queen” or “Terror Queen,” is a case in point. One way to understand her is as a Celtic Valkyrie: a bird-woman (crow or raven) who screams onto the battlefield, choosing and claiming the dead. (The banshee of Irish legend is probably an aspect or echo of the Morrigan.) The Morrígna, plural, are supernatural phantoms who augur death, just like the Valkyries. The Morrigan is also connected to the earth and fertility, reminiscent of the way the Germanic Freyja manages to be both angel of death and goddess of love. But where Freyja is generally a positive goddess, associated with joy and abundance, the Morrigan tends to be rather scary and dark.

Think we should add a Morrigan costume to Take Back Halloween? If you missed our Kickstarter campaign you can still become a supporter and get to vote on the new costumes.

Illustration credit: The wonderful painting of the Morrigan is by Brigid Ashwood.

Thanks to our Kickstarter campaign for 2013, we’re adding 19 new costumes this season, 7 of which our backers and supporters will get to vote on. This series of posts is designed to briefly introduce the many notable women and legendary figures we’ll be considering. Voting will take place spring/summer of 2013.

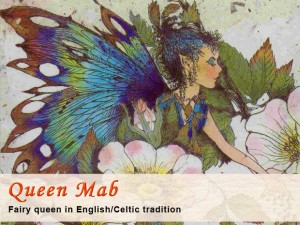

“I see Queen Mab hath been with you,” says Mercutio to Romeo, thus beginning one of Shakespeare’s most famous speeches:

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate-stone

On the fore-finger of an alderman,

Drawn with a team of little atomies

Athwart men’s noses as they lie asleep;

Her wagon-spokes made of long spiders’ legs,

The cover of the wings of grasshoppers,

The traces of the smallest spider’s web,

The collars of the moonshine’s watery beams,

Her whip of cricket’s bone, the lash of film,

Her wagoner a small grey-coated gnat,

Not so big as a round little worm

Prick’d from the lazy finger of a maid;

Her chariot is an empty hazel-nut

Made by the joiner squirrel or old grub,

Time out o’ mind the fairies’ coachmakers.

So, she’s small.

Where did this tiny personage come from? Did Shakespeare invent her? The name “Mab” is Welsh, and may represent an echo of pre-Christian Celtic mythology. In Ireland the great goddess Medb was transformed into the legendary Queen Medb, cattle thief extraordinaire. It’s quite possible that the same Celtic goddess underwent a similar downsizing in Wales—except instead of becoming a mortal queen, she became a fairy. Whatever the case, it’s likely that Shakespeare was drawing on existing tradition in the folklore of the British Isles.

Think we should add a Queen Mab costume to Take Back Halloween? If you missed our Kickstarter campaign you can still become a supporter and get to vote on the new costumes.

Illustration credit: The beautiful fairy painting is “The Spell Fairy” by Welsh artist Trudi Finch. It’s available as a greeting card in her shop (click the link), along with her other gorgeous work.

Jane Austen (1775-1817) hardly needs an introduction; she is one of the most beloved and admired authors in the English language. The watercolor above right is by her sister Cassandra, and is believed to be of Jane. The portrait of Jane on the left is a 19th century painting based on a sketch by Cassandra.

Talk Like Jane Austen Day is October 30, so you can get double duty out of your Halloween costume. To dress like Jane Austen, you just need a Regency gown. And some sort of headcovering—her niece said she always wore a cap (presumably under her bonnet when she went outdoors).

The pieces we suggest, from left to right:

1. Custom Regency gown. This seller will make a gown to your measurements, with your choice of fabric and trim. There are now many, many other sellers on Etsy offering Regency gowns (that wasn’t the case when we originally published this costume in 2011), so shop around to find an option that suits your taste and your budget.

2. Regency bonnet. This is the Eliza model from Austentation, which offers a wide range of Regency bonnets and hats. You can get any of them plain or decorated with your choice of fabric, feathers, ribbon, etc., and all at very reasonable prices.

3. Cap. Wear this by itself or underneath the bonnet. This is a simple period cap in white, with a little frill to frame your face.

4. Isotoner satin ballet slippers. Regency shoes were extremely similar to ballet slippers; they even had ribbons. Modern Isotoners are an excellent substitute.

5. Single strand 18-inch faux pearl necklace. Regency pearls were simple and classic-looking. If you don’t already have a basic pearl/faux pearl necklace, this one will do.